What's in this article?

- 1 What is Bladder cancer?

- 2 Types of Bladder Cancer

- 3 Transitional cell (urothelial) carcinoma

- 4 Other cancers that start in the bladder

- 5 Causes of Bladder Cancer

- 6 Signs and Symptoms of Bladder Cancer

- 7 Symptoms of advanced bladder cancer

- 8 Risk Factors of Bladder Cancer

- 9 Bladder Cancer Diagnosis

- 10 Staging

- 11 Treatment for Bladder Cancer

- 12 Prevention for Bladder Cancer

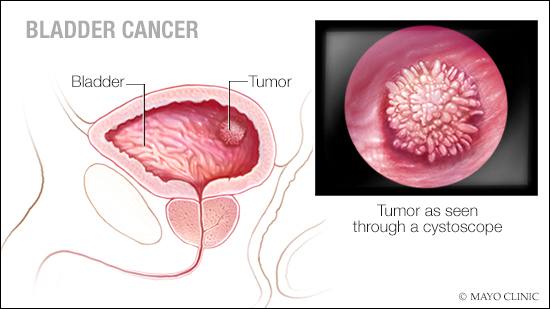

What is Bladder cancer?

Bladder cancer is a cancer that forms in tissues of the bladder, the organ that stores urine. Rarely the bladder is involved by non-epithelial cancers, such as lymphoma or sarcoma, but these are not ordinarily included in the colloquial term bladder cancer. It is a disease in which abnormal cells multiply without control in the bladder.

Types of Bladder Cancer

Bladder cancers are divided into several types based how their cells look under a microscope. Different types can respond differently to treatments.

Transitional cell (urothelial) carcinoma

This is by far the most common type of bladder cancer. More than 9 out of 10 bladder cancers are this type. The cells from transitional cell carcinomas (TCCs) look like the urothelial cells that line the inside of the bladder.

Urothelial cells also line other parts of the urinary tract, such as the lining of the kidneys (called the renal pelvis), the ureters, and the urethra, so TCCs can also occur in these places. In fact, patients with bladder cancer sometimes have other tumors in the lining of the kidneys, ureters, or urethra. If someone has a cancer in one part of their urinary system, the entire urinary tract needs to be checked for tumors.

Bladder cancers are often described based on how far they have invaded into the wall of the bladder:

- Non-invasive bladder cancers are still in the inner layer of cells (the transitional epithelium) but have not grown into the deeper layers.

- Invasive cancers grow into the lamina propria or even deeper into the muscle layer. Invasive cancers are more likely to spread and are harder to treat.

A bladder cancer can also be described as superficial or non-muscle invasive. These terms include both non-invasive tumors as well as any invasive tumors that have not grown into the main muscle layer of the bladder.

Transitional cell carcinomas are also divided into 2 subtypes, papillary and flat, based on how they grow:

- Papillary carcinomas grow in slender, finger-like projections from the inner surface of the bladder toward the hollow center. Papillary tumors often grow toward the center of the bladder without growing into the deeper bladder layers. These tumors are called non-invasive papillary cancers. Very low-grade, non-invasive papillary cancer is sometimes called papillary neoplasm of low-malignant potential and tends to have a very good outcome.

- Flat carcinomas do not grow toward the hollow part of the bladder at all. If a flat tumor is only in the inner layer of bladder cells, it is known as a non-invasive flat carcinoma or a flat carcinoma in situ (CIS).

If either a papillary or flat tumor grows into deeper layers of the bladder, it is called an invasive transitional cell (or urothelial) carcinoma.

Other cancers that start in the bladder

- Squamous cell carcinoma: In the United States, only about 1% to 2% of bladder cancers are squamous cell carcinomas. Under a microscope, the cells look much like the flat cells that are found on the surface of the skin. Nearly all squamous cell carcinomas are invasive.

- Adenocarcinoma: Only about 1% of bladder cancers are adenocarcinomas. The cancer cells have a lot in common with gland-forming cells of colon cancers. Nearly all adenocarcinomas of the bladder are invasive.

- Small cell carcinoma: Less than 1% of bladder cancers are small-cell carcinomas, which start in nerve-like cells called neuroendocrine cells. These cancers often grow quickly and typically need to be treated with chemotherapy like that used for small cell carcinoma of the lung.

- Sarcoma: Sarcomas start in the muscle cells of the bladder, but they are rare.

These less common types of bladder cancer (other than sarcoma) are treated similar to transitional cell cancers, especially for early stage tumors, but different drugs may be needed if chemotherapy is required.

Causes of Bladder Cancer

Bladder cancer has been linked to smoking, a parasitic infection, radiation and chemical exposure.

Tobacco smoking is the main known contributor to urinary bladder cancer; in most populations, smoking is associated with over half of bladder cancer cases in men and one-third of cases among women. There is a linear relationship between smoking and risk, and quitting smoking reduces the risk. Passive smoking has not been proven to be involved.

In a 10-year study involving almost 48,000 men, researchers found that men who drank 1.5 liters of water per day had a significantly reduced incidence of bladder cancer when compared with men who drank less than 240mL (around 1 cup) per day. The authors proposed that bladder cancer might partly be caused by the bladder directly contacting carcinogens that are excreted in urine, although this has not yet been confirmed in other studies.

Thirty percent of bladder tumors probably result from occupational exposure in the workplace to carcinogens such as benzidine. 2-Naphthylamine, which is found in cigarette smoke, has also been shown to increase bladder cancer risk. Occupations at risk are bus drivers, rubber workers, motor mechanics, leather (including shoe) workers, blacksmiths, machine setters, and mechanics. Hairdressers are thought to be at risk as well because of their frequent exposure to permanent hair dyes.

It has been suggested that mutations at HRAS, KRAS2, RB1, and FGFR3 may be associated in some cases.

Bladder cancer develops when cells in the bladder begin to grow abnormally. Rather than grow and divide in an orderly way, these cells develop mutations that cause them to grow out of control and not die. These abnormal cells form a tumor.

Signs and Symptoms of Bladder Cancer

Bladder cancer can often be found early because it causes blood in the urine or other urinary symptoms.

Blood in the urine

In most cases, blood in the urine (called hematuria) is the first warning sign of bladder cancer. Sometimes, there is enough blood to change the color of the urine. Depending on the amount of blood, the urine may be orange, pink, or, less often, darker red. Sometimes, the color of the urine is normal but small amounts of blood are found when a urine test (urinalysis) is done because of other symptoms or as part of a general medical checkup.

Blood may be present one day and absent the next, with the urine remaining clear for weeks or months. If a person has bladder cancer, blood eventually reappears. Usually, the early stages of bladder cancer cause bleeding but little or no pain or other symptoms.

Blood in the urine does not always mean you have bladder cancer. More often it is caused by other things like an infection, benign (non-cancerous) tumors, stones in the kidney or bladder, or other benign kidney diseases. But it is important to have it checked by a doctor so the cause can be found.

Changes in bladder habits or symptoms of irritation

Bladder cancer can sometimes cause changes in urination, such as:

- Having to urinate more often than usual

- Pain or burning during urination

- Feeling as if you need to go right away, even when the bladder is not full

These symptoms are also more likely to be caused by a benign condition such as infection, bladder stones, an overactive bladder, or an enlarged prostate (in men). Still, it is important to have them checked by a doctor so that the cause can be found and treated, if needed.

Symptoms of advanced bladder cancer

Bladder cancers that have grown large enough or have spread to other parts of the body can sometimes cause other symptoms, such as:

- Being unable to urinate

- Lower back pain on one side

- Loss of appetite and weight loss

- Swelling in the feet

- Bone pain

If there is a reason to suspect you might have bladder cancer, the doctor will use one or more exams or tests to find out if it is cancer or something else.

Risk Factors of Bladder Cancer

- Smoking. Smoking cigarettes, cigars or pipes may increase your risk of bladder cancer by causing harmful chemicals to accumulate in your urine. When you smoke, your body processes the chemicals in the smoke and excretes some of them in your urine. These harmful chemicals may damage the lining of your bladder, which can increase your risk of cancer.

- Increasing age. Your risk of bladder cancer increases as you age. Bladder cancer can occur at any age, but it’s rarely found in people younger than 40.

- Being white. Whites have a greater risk of bladder cancer than do people of other races.

- Being a man. Men are more likely to develop bladder cancer than women are.

- Exposure to certain chemicals. Your kidneys play a key role in filtering harmful chemicals from your bloodstream and moving them into your bladder. Because of this, it’s thought that being around certain chemicals may increase your risk of bladder cancer. Chemicals linked to bladder cancer risk include arsenic and chemicals used in the manufacture of dyes, rubber, leather, textiles and paint products.

- Previous cancer treatment. Treatment with the anti-cancer drug cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan) increases your risk of bladder cancer. People who received radiation treatments aimed at the pelvis for a previous cancer may have an elevated risk of developing bladder cancer.

- Taking a certain diabetes medication. People who take the diabetes medication pioglitazone (Actos) for more than a year may have an increased risk of bladder cancer. Other diabetes medications contain pioglitazone, including pioglitazone and metformin (Actoplus Met) and pioglitazone and glimepiride (Duetact).

- Chronic bladder inflammation. Chronic or repeated urinary infections or inflammations (cystitis), such as may happen with long-term use of a urinary catheter, may increase your risk of a squamous cell bladder cancer. In some areas of the world, squamous cell carcinoma is linked to chronic bladder inflammation caused by the parasitic infection known as schistosomiasis.

- Personal or family history of cancer. If you’ve had bladder cancer, you’re more likely to get it again. If one or more of your immediate relatives have a history of bladder cancer, you may have an increased risk of the disease, although it’s rare for bladder cancer to run in families. A family history of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer, also called Lynch syndrome, can increase your risk of cancer in your urinary system, as well as in your colon, uterus, ovaries and other organs.

Bladder Cancer Diagnosis

Bladder cancer is most frequently diagnosed on investigating the cause of bleeding in the urine that a patient has noticed. The following are investigations or tests that come in handy in such circumstances:

- Urinalysis: A simple urine test that can confirm that there is bleeding in the urine and can also provide an idea about whether an infection is present or not. It is usually one of the first tests that is asked for by a physician. It does not confirm that a person has bladder cancer but can help the physician in short listing the potential causes of bleeding.

- Urine cytology: This test is performed on a urine sample which is centrifuged and the sediment is examined under the microscope by a pathologist. The idea is to detect malformed cancerous cells that may be shed into the urine by a cancer. A positive test is quite specific for cancer (for example, it provides a high degree of certainty that cancer is present in the urinary system). However, many early bladder cancers may be missed by this test so a negative or inconclusive test doesn’t effectively rule out the presence of bladder cancer.

- Ultrasound: An ultrasound examination of the bladder can detect bladder tumors. It can also detect the presence of swelling in the kidneys in case the bladder tumor is located at a spot where it can potentially block the flow of urine from the kidneys to the bladder. It can also detect other causes of bleeding, such as stones in the urinary system or prostate enlargement, which may be the cause of the symptoms or may coexist with a bladder tumor.

- CT scan/MRI: A CT scan or MRI provides greater visual detail than can be afforded by an ultrasound exam and may detect smaller tumors in the kidneys or bladder than can be detected by an ultrasound. It can also detect other causes of bleeding more effectively than ultrasound especially when intravenous contrast is used.

- Cystoscopy and biopsy: This is probably the single most important investigation for bladder cancer. Since there is always a chance to miss bladder tumors on imaging investigations (ultrasound/CT/MRI) and urine cytology, it is recommended that all patients with bleeding in the urine, without an obvious cause, should have a cystoscopy performed by a urologist as a part of the initial evaluation. This entails the use of a thin tube-like optical instrument connected to a camera and a light source (cystoscope). It is passed through the urinary passage into the bladder and the inner surface of the bladder is visualized on a video monitor. Small or flat tumors which may not be visible on other investigations can be seen by this method and a piece of this tissue can be taken as a biopsy for examination under the microscope. The presence and type of bladder cancer can be diagnosed most effectively by this method.

- Newer biomarkers like NMP 22 and fluorescent in-situ hybridization (FISH) are currently in use to detect bladder cancer cells by a simple urine test. However, they have not yet achieved the level of accuracy to replace cystoscopy and cytology in the diagnosis and follow-up of bladder cancer.

Staging

The tumor or the T stage is accorded by a pathological examination of the tumor specimen removed surgically. This refers to the depth of penetration of the tumor from the innermost lining to the deeper layers of the bladder.

The T stages are as follows:

- Tx – Primary tumor cannot be evaluated

- T0 – No primary tumor

- Ta – Noninvasive papillary carcinoma (tumor limited to the innermost lining or the epithelium)

- Tis – Carcinoma in situ (flat tumor)

- T1 – Tumor invades connective tissue under the epithelium (surface layer)

- T2 – Tumor invades muscle of the bladder

- T2a – Superficial muscle affected (inner half)

- T2b – Deep muscle affected (outer half)

- T3 – Tumor invades perivesical (around the bladder) fatty tissue

- T3a – microscopically (visible only on examination under the microscope)

- T3b – macroscopically (for example, visible tumor mass on the outer bladder tissue)T4 – Tumor invades any of the following: prostate, uterus, vagina, pelvic wall, or abdominal wall

The node or the N stage is determined by the presence and extent of involvement of the lymph nodes in the pelvic region of the body near the urinary bladder.

The N stages are as follows:

- Nx – Regional lymph nodes cannot be evaluated

- N0 – No regional lymph node metastasis

- N1 – Metastasis in a single lymph node < 2 cm in size

- N2 – Metastasis in a single lymph node > 2 cm, but < 5 cm in size, or multiple lymph nodes < 5 cm in size N3 – Metastasis in a lymph node > 5 cm in size

The metastases or the M stage signifies the presence or absence of the spread of bladder cancer to other organs of the body.

- Mx – Distant metastasis cannot be evaluated

- M0 – No distant metastasis

- M1 – Distant metastasis

The proper staging of bladder cancer is an essential step which has significant bearings on the management of this condition. The implications of bladder stage are:

- It helps select proper treatment for the patient. Superficial disease (Ta/T1/Tis) can generally be managed with less aggressive treatment as compared to invasive disease (T2/T3/T4).

- Invasive tumors have a higher likelihood of spread to lymph nodes and distant organs as compared to superficial tumors.

- The chances of cure and long-term survival progressively decrease as the bladder cancer stage increases.

- Staging allows proper classification of patients into groups for research studies and study of newer treatments.

Treatment for Bladder Cancer

The choice of treatment and the long-term outcome (prognosis) for people who have bladder cancer depend on the stage and grade of cancer. When deciding about your treatment, your doctor also considers your age, overall health, and quality of life.

Bladder cancer has a better chance of being treated successfully if it is found early.

Treatment choices for bladder cancer may include:

- Surgery to remove the cancer. Surgery, either alone or along with other treatments, is used in most cases.

- Chemotherapy to destroy cancer cells using medicines. Chemotherapy may be given before or after surgery.

- Radiation therapy to destroy cancer cells using high-dose X-rays or other high-energy rays. Radiation therapy may also be given before or after surgery and may be given at the same time as chemotherapy.

- Immunotherapy. This treatment causes your body’s natural defenses, known as your immune system, to attack bladder cancer cells. For more information, see Medications.

Prevention for Bladder Cancer

Although there’s no guaranteed way to prevent bladder cancer, you can take steps to help reduce your risk. For instance:

- Don’t smoke. Not smoking means that cancer-causing chemicals in smoke can’t collect in your bladder. If you don’t smoke, don’t start. If you smoke, talk to your doctor about a plan to help you stop. Support groups, medications and other methods may help you quit.

- Take caution with chemicals. If you work with chemicals, follow all safety instructions to avoid exposure.

- Drink water throughout the day. In theory, drinking liquids, especially water, may dilute toxic substances that may be concentrated in your urine and flush them out of your bladder more quickly. Studies have been inconclusive as to whether drinking water will decrease your risk of bladder cancer.

- Choose a variety of fruits and vegetables. Choose a diet rich in a variety of colorful fruits and vegetables. The antioxidants in fruits and vegetables may help reduce your risk of cancer.