What's in this article?

What is Malaria?

Malaria is a mosquito-borne disease caused by a parasite. People with malaria often experience fever, chills, and flu-like illness. Left untreated, they may develop severe complications and die. In 2013 an estimated 198 million cases of malaria occurred worldwide and 500,000 people died, mostly children in the African Region. About 1,500 cases of malaria are diagnosed in the United States each year. The vast majority of cases in the United States are in travelers and immigrants returning from countries where malaria transmission occurs, many from sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia.

Fast facts on Malaria

Here are some key points on malaria. More detail and supporting information is in the main article.

- Malaria was first identified in 1880 as a disease caused by parasitic infection

- The name of the disease comes from the Italian word mal’aria, meaning “bad air”

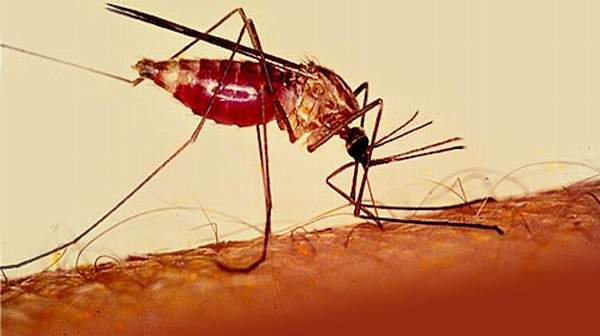

- Malaria is transmitted to humans through bites by infected mosquitoes

- The most common time for these mosquitoes to be active is between dusk and dawn

- Worldwide, there were an estimated 198 million cases of malaria in 2013 and 584,000 deaths

- Malaria occurs mostly in poor, tropical and subtropical areas of the world

- Malaria was eliminated from the US in the early 1950s, but the mosquitos that carry and transmit the malaria parasite still remain, creating a constant risk of reintroduction

- Reported malaria cases in the US reached a 40-year high of 1,925 in 2011

- A malaria vaccine for humans is close to being approved for use in Europe

- An estimated 3.4 billion people in 106 countries and territories are at risk of malaria – nearly half of the world’s population

- Annual funding for malaria control in 2013 was three times the amount spent in 2005, yet it represented only 53% of global funding needs

- Malaria incidence rates are estimated to have fallen by 30% globally between 2000 and 2013 while estimated mortality rates fell by 47%

- The World Health Organization (WHO) has set out to reduce all malaria cases and deaths by 90% by 2030

What Causes Malaria?

Malaria can occur if a mosquito infected with thePlasmodium parasite bites you. An infected mother can also pass the disease to her baby at birth. This is known as congenital malaria. Malaria is transmitted by blood, so it can also be transmitted through:

- an organ transplant

- a transfusion

- use of shared needles or syringes

Symptoms of Malaria

In the early stages, malaria symptoms are sometimes similar to those of many other infections caused by bacteria, viruses, or parasites. Symptoms may include:

- Fever.

- Chills.

- Headache.

- Sweats.

- Fatigue.

- Nausea and vomiting.

Symptoms may appear in cycles. The time between episodes of fever and other symptoms varies with the specific parasite you are infected with. Episodes of symptoms may occur:

- Every 48 hours if you are infected with P. vivax or P. ovale.

- Every 72 hours if you are infected with P. malariae.

P. falciparum does not usually cause a regular, cyclic fever.

The cyclic pattern of malaria symptoms is due to the life cycle of malaria parasites as they develop, reproduce, and are released from the red blood cells and liver cells in the human body. This cycle of symptoms is also one of the major signs that you are infected with malaria.

Treatment for Malaria

Malaria, especially falciparum malaria, is a medical emergency that requires a hospital stay. Chloroquine is often used as an anti-malarial drug. But chloroquine-resistant infections are common in some parts of the world.

Possible treatments for chloroquine-resistant infections include:

- Artemisinin derivative combinations, including artemether and lumefantrine

- Atovaquone-proguanil

- Quinine-based regimen, in combination with doxycycline or clindamycin)

- Mefloquine, in combination with artesunate or doxycycline

The choice of drug depends, in part, on where you got the infection.

Medical care, including fluids through a vein (IV) and other drugs and breathing (respiratory) support may be needed.

Vaccines for Malaria

Research is ongoing to develop safe and effective vaccines for malaria, with one vaccine close to being licensed for use in Europe.

The development of an effective malaria vaccine poses major challenges as a comprehensive vaccine would need to be effective against a number of strains of malaria parasites. As such, the majority of vaccines in development are focused on the most serious and deadly parasite, Plasmodium falciparum. The development of a vaccine against P. vivax is complicated by the associated relapses and hypnozoite stages of infection with this parasite.

The malaria vaccine that may soon be approved for use in humans is called RTS,S/AS01 and was developed through a partnership between GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals (GSK) and the PATH Malaria Vaccine Initiative (MVI), with support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

This vaccine has completed Phase III testing and, in 2015, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) issued “a European scientific opinion” that indicated that they had assessed the vaccine as favourable in terms of its risk/benefit from a regulatory perspective. Although the vaccine is not licensed or approved for use in Europe, this statement may help regulatory authorities in Africa reach a decision on licensure.11

This vaccine is effective against P. falciparum only; it affords no protection against P. vivax malaria.

The malaria vaccine has been tested for efficacy in 5-17 month old children and 6-12 week old infants. Researchers found that the vaccine was 39% effective in the older children who received four doses on a 0, 1, 2, 20 month schedule. The vaccine was 31.5% effective against severe malaria in these 5-17 month old children, but no protection was conferred against severe malaria if children did not receive the fourth dose.

In the younger infants (6-12 weeks), the vaccine was 27% effective when the first three doses were given at 6, 10 and 14 weeks of age, and a fourth dose 18 months later. The vaccine was 18% effective in the children who did not receive the fourth dose. The vaccine was not seen to be effective against severe malaria in this age group, however.

Testing revealed some unexplained phenomenon in those children receiving the vaccine, including an increase in febrile seizures, meningitis and cerebral malaria. It is not yet known if these issues are related to the vaccine itself or are due to some other cause.