What's in this article?

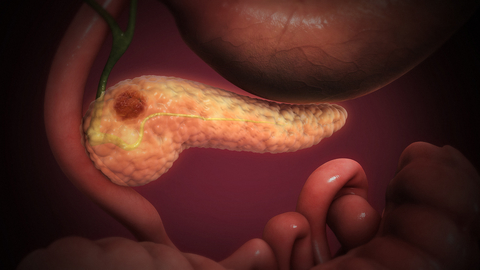

Pancreatic cancer begins in the tissues of your pancreas an organ in your abdomen that lies horizontally behind the lower part of your stomach. Your pancreas secretes enzymes that aid digestion and hormones that help regulate the metabolism of sugars.

Pancreatic cancer often has a poor prognosis, even when diagnosed early. Pancreatic cancer typically spreads rapidly and is seldom detected in its early stages, which is a major reason why it’s a leading cause of cancer death. Signs and symptoms may not appear until pancreatic cancer is quite advanced and complete surgical removal isn’t possible.

Causes of pancreatic cancer

Cancer is ultimately the result of cells that uncontrollably grow and do not die. Normal cells in the body follow an orderly path of growth, division, and death. Programmed cell death is called apoptosis, and when this process breaks down, cancer results. Pancreatic cancer cells do not experience programmatic death, but instead continue to grow and divide. Although scientists do not know exactly what causes these cells to behave this way, they have identified several potential risk factors.

Genes – the DNA type

Cells can experience uncontrolled growth if there is damage or mutations in the DNA, and therefore, damage to the genes involved in cell division. Four key types of genes are responsible for the cell division process: oncogenes tell cells when to divide, tumor suppressor genes tell cells when not to divide, suicide genes control apoptosis and tell cells to kill themselves if something goes wrong, and DNA-repair genes instruct cells to repair damaged DNA.

Cancer occurs when a cell’s gene mutations make the cell unable to correct DNA damage and unable to commit suicide. Similarly, cancer is a result of mutations that inhibit oncogene and tumor suppressor gene functions, leading to uncontrollable cell growth. If you have DNA mutations of oncogenes or tumor suppressor genes that lead to pancreatic cancer, it is likely that the mutation was a result of factors that affected DNA after you were born rather than a result of inheritance from parents.

Genes – the family type

Cancer can be the result of a genetic predisposition that is inherited from family members. It is possible to be born with certain genetic mutations or a fault in a gene that makes one statistically more likely to develop cancer later in life. About 10% of pancreatic cancers are though to be caused by inherited gene mutations. Genetic syndromes that are associated with pancreatic cancer include hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome, melanoma, pancreatitis, and non-polyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome).

Carcinogens

Carcinogens are a class of substances that are directly responsible for damaging DNA, promoting or aiding cancer. Certain pesticides, dyes, and chemicals used in metal refining are thought to be carcinogenic, increasing the risk of developing pancreatic cancer. When our bodies are exposed to carcinogens, free radicals are formed that try to steal electrons from other molecules in the body. Theses free radicals damage cells, affecting their ability to function normally, and the result can be cancerous growths.

Other medical factors

As we age, there is an increase in the number of possible cancer-causing mutations in our DNA. This makes age an important risk factor for pancreatic cancer, especially for those over the age of 60. There are several other diseases that have been associated with an increased risk of cancer of the pancreas.

These include cirrhosis or scarring of the liver, helicobacter pylori infection (infection of the stomach with the ulcer-causing bacteria H. pylori), diabetes mellitus, chronic pancreatitis (inflammation of the pancreas), and gingivitis or periodontal disease.

Pancreatic Cancer Risk factors

- African-American race

- Excess body weight

- Chronic inflammation of the pancreas (pancreatitis)

- Diabetes

- Family history of genetic syndromes that can increase cancer risk, including a BRCA2 gene mutation, Lynch syndrome and familial atypical mole-malignant melanoma (FAMMM)

- Personal or family history of pancreatic cancer

- Smoking

Pancreatic Cancer Symptoms

Pancreatic cancer often goes undetected until it’s advanced and difficult to treat. In the vast majority of cases, symptoms only develop after pancreatic cancer has grown and begun to spread.

Because more than 95% of pancreatic cancer is the adenocarcinoma type, we’ll describe those symptoms first, followed by symptoms of rare forms of pancreatic cancer.

Pancreatic Cancer Symptoms: Location Matters

Initially, pancreatic cancer tends to be silent and painless as it grows. By the time it’s large enough to cause symptoms, pancreatic cancer has generally grown outside the pancreas. At this point, symptoms depend on the cancer’s location within the pancreas:

- Pancreatic cancer in the head of the pancreas tends to cause symptoms such as weight loss, jaundice (yellow skin), dark urine, light stool color, itching, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, back pain, and enlarged lymph nodes in the neck.

- Pancreatic cancer in the body or tail of the pancreas usually causes belly and/or back pain and weight loss.

In general, symptoms appear earlier from cancers in the head of the pancreas, compared to those in the body and tail.

Pancreatic Cancer and Gastrointestinal Symptoms

Because pancreatic cancer grows around important areas of the digestive system, gastrointestinal symptoms often predominate:

- Abdominal pain. More than 80% of people with pancreatic cancer eventually experience some abdominal pain as the tumor grows. Pancreatic cancer can cause a dull ache in the upper abdomen radiating to the back. The pain may come and go.

- Bloating. Some people with pancreatic cancer have a sense of early fullness with meals (satiety) or an uncomfortable swelling in the abdomen.

- Nausea

- Diarrhea

- Pale-colored stools. If the duct draining bile into the intestine is blocked by pancreatic cancer, the stools may lose their brown color and become pale or clay-colored. Urine may become darker.

Pancreatic Cancer: Whole-Body Symptoms

As it grows and spreads, pancreatic cancer affects the whole body. Such symptoms can include:

- Weight loss

- Malaise

- Loss of appetite

- Elevated blood sugars. Some people with pancreatic cancer develop diabetes as the cancer impairs the pancreas’ ability to produce insulin. (However, the vast majority of people with a new diagnosis of diabetes do not have pancreatic cancer.)

Treating Pancreatic Cancer

Treatment for pancreatic cancer depends on the type, location and stage of your cancer (how far it’s spread).

Your age, general health and personal preferences will also be taken into consideration when deciding on your treatment plan.

The first aim will be to completely remove the tumour and any other cancerous cells in your body.

If this isn’t possible, the focus will be on preventing the tumour growing and causing further harm.

Sometimes it’s not possible to get rid of the cancer or slow it down, so treatment will aim to relieve your symptoms and make you as comfortable as possible.

Cancer of the pancreas is very difficult to treat. In its early stages, this type of cancer rarely causes symptoms, so it’s often not detected until it’s quite advanced. If the tumour is large or has spread, treating or curing the cancer is much harder.

Discussing your treatment

Deciding what treatment is best for you can be a difficult process. There’s a lot to take in, so it’s important to talk about the possible alternatives with a family member or friend.

You should also have an in-depth discussion with your doctor, who can tell you the pros and cons of the treatments available to you.

If at any stage you don’t understand the treatment options being explained to you, make sure you ask your doctor for more details.

There are three main ways that cancer of the pancreas can be treated:

- surgery

- chemotherapy

- radiotherapy

Some types of pancreatic cancer only require one form of treatment, whereas others may require two or a combination of all three.

Surgery

Surgery is usually the only way pancreatic cancer can be completely cured. However, as the condition is usually advanced by the time it’s diagnosed, surgery is only suitable for around 15-20% of people.

However, this isn’t a suitable option if your tumour has wrapped itself around important blood vessels. If your cancer has spread to other areas of the body, surgically removing the tumour won’t cure you.

Surgery for pancreatic cancer is usually only an option for people who have a good general level of health. This is because pancreas surgery is often long and complex, and the recovery process can be slow.

Sometimes the risks of surgery can outweigh the potential benefits.

Your doctor will discuss with you whether surgery is a suitable option. There are several possible surgical procedures, which are outlined below.

Whipple procedure

The Whipple procedure is the most common operation used to treat pancreatic cancer, and involves removing the head of the pancreas.

Your surgeon must also remove the first part of your small intestine (bowel), your gall bladder (which stores bile) and part of your bile duct. Sometimes, part of the stomach also has to be removed.

The end of the bile duct and the remaining part of your pancreas is connected to your small intestine. This allows bile and the hormones and enzymes produced by the pancreas to still be released into your system.

After this type of surgery, about one in three people need to take enzymes to help them digest food.

The Whipple procedure involves long and intensive surgery, but it’s easier to recover from than a total pancreatectomy (see below).

Distal pancreatectomy

A distal pancreatectomy involves removing the tail and body of your pancreas.

Your spleen will usually also be removed at the same time. Part of your stomach, bowel, left adrenal gland, left kidney and left diaphragm (the muscle that separates the chest cavity from the abdomen) may also be removed.

Like the Whipple procedure, a distal pancreatectomy is a long and complex operation that won’t be carried out unless your doctor thinks it’s necessary.

Total pancreatectomy

During a total pancreatectomy, your entire pancreas will be removed. This is sometimes necessary due to the position of the tumour.

Your surgeon will also remove your:

- bile duct

- gall bladder

- spleen

- part of your small intestine

- part of your stomach (sometimes)

- surrounding lymph nodes (part of the immune system)

After a total pancreatectomy, you’ll need to take enzymes to help your digestive system digest food. You’ll also have diabetes for the rest of your life because the pancreas produces insulin the hormone that regulates blood sugar.

Removing your spleen can increase your risk of developing infections and may also affect your blood’s ability to clot. This means you’ll be on penicillin (or an alternative antibiotic if you’re allergic to it) for the rest of your life, and you’ll need to have regular vaccinations.

Sometimes, you may need to take tablets for a short period to stop the platelets in your blood sticking to each other. Platelets are a type of blood cell that cause your blood to clot (thicken).

Surgery to ease your symptoms

Although surgery may not be a suitable way of removing your tumour, you may be offered it to help ease your symptoms.

This type of surgery won’t cure your cancer, but will mean that your condition is easier to manage, and it will make you more comfortable.

To help control jaundice, a stent can be placed in your bile duct using endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). This will help keep the bile duct open and prevent bilirubin the yellow chemical in bile from building up and causing jaundice.

If a stent isn’t a suitable option for you, you may need an operation to bypass your blocked bile duct. Your surgeon will cut the bile duct just above the blockage and reconnect it to your intestine, which allows your bile to drain away.

These types of surgery are much less intensive than surgery carried out on the pancreas. The recovery time is much quicker, and people find that their jaundice improves significantly.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is a type of cancer treatment that uses anti-cancer medicines to either kill the cancerous (malignant) cells in your body or stop them multiplying.

Chemotherapy treatment is often used alongside surgery and radiotherapy (see below) to help ensure that as much of the cancer is treated as possible.

Chemotherapy may be given:

- before surgery – to try to shrink the cancer, so there’s a greater chance of the surgeon being able to remove all of the cancer

- after surgery – to help reduce the risk of the cancer coming back

- when surgery isn’t possible – to try to shrink the cancer, slow its growth and relieve your symptoms

Some chemotherapy medicines can be taken orally (by mouth), but some need to be given directly into a vein (intravenously).

Chemotherapy also attacks normal, healthy cells, which is why this type of treatment can have many side effects. The most common side effects include:

- vomiting

- nausea

- mouth sores

- fatigue

- increased risk of infection

These are usually only temporary, and should improve once you’ve completed your treatment.

The chemotherapy medications can also be used in combination, so your doctor may suggest using one medication or a combination of two or three.

Combining chemotherapy medications can give a better chance of shrinking or controlling the cancer, but increases the chance of side effects. Sometimes, the risks of chemotherapy can outweigh the potential benefits.

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy is a form of cancer therapy that uses high-energy beams of radiation to help shrink your tumour and relieve pain.

Side effects of radiotherapy can include:

- fatigue

- skin rashes

- loss of appetite

- diarrhoea

- nausea or vomiting

These side effects are usually only temporary, and should improve after your treatment has been completed.